The Salicaceae or Willow family is now a much larger family.

It just used to include the willows, poplar, aspen, and cottonwoods.

Genetic studies summarized by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG) have greatly expanded the circumscription of the family to contain 56 genera and about 1220 species, including the Scyphostegiaceae and many of the former Flacourtiaceae.

BUT; fortunately for us, in the British Isles it has only two main genera, namely the Poplar and the Willow. Although the flowers (as always in traditional classification) determine the ultimate genus and whether it is a Willow or Poplar, most of us can easily tell the difference from the leaves. All the Poplars have a triangular, broad oval, to heart-shape outline with often a long leaf stem (petiole) whilst most of the Willows have long, narrow leaves or roundish, much smaller leaves than Poplars.

When there are no leaves in winter the tree could be identified by the winter buds, where Willows just have one outer scale and the Poplar has several. However as there is much to say about the Willow, I will leave the Poplar for another blog in the future!

Pictures by Matt Summers and Mike Poulton unless stated. The links provided on the scientific and common plant names provide more detailed information as well as good pictures on each species. Also special thanks to PFAF which provides a wonderful plant database of not just native plants but any useful plants all over the world.

There are links on the Scientific name from the Plant Atlas Online and I also copied the general ecological information from them. Wikipedia or other websites provide more information about the uses, etc.

Contents

Classification of the Willows

Section 1: SALIX

- Salix pentandra or Bay Willow

- S. x meyeriana (Salix fragilis x pentandra) or Shiny-leaved Willow

- S. euxina or Crack Willow + nbn atlas

- S. x fragilis or Hybrid Crack Willow

- S. alba or White Willow (archaeophyte)

- S. triandra or Almond Willow (arch.)

- S. x mollissima (Salix triandra x viminalis) or Sharp-stipuled Willow (arch.)

Section 2: VETRIX

- S. purpurea or Purple Willow

- S. viminalis or Osier (arch.)

- S. x smithiana (Salix cinerea x viminalis) or Broad-leaved Osier

- S. x calodendron (Salix caprea x cinerea x viminalis ) or Holme Willow

- S. x stipularis (Salix aurita x caprea x viminalis) or Eared Osier

- S. x holosericea (Salix viminalis x cinerea) or Silky-leaved Osier

- S. x fruticosa (Salix aurita x viminalis) or Shrubby Osier

Section 3: CHAMAETIA

- S. myrsinites or Whortle Leaved Willow

- S. herbacea or Dwarf Willow

- S. reticulata or Net Leaved Willow

Classification of the Willows:

“ Identification is often made difficult by the extensive degree of hybridisation” (68 combinations at present known in B.I., of which 20 are hybrids between 3 species). Only those hybrids considered certainly or very probably correctly identified are listed in Stace.

Hybrids can also be formed due to us planting Willows as an ornamental or for basketry in vicinity of other native Willows.

Catkins and both young and mature leaves (collected in July- September) are desirable for correct identification.

The genus Salix or Willow is separated in 3 sections. As always in classification the species in each section have things in common.

The first Section is SALIX and has 10 species of which 5 can be said to be true natives and 2 are archaeophytes. They are all trees or tall shrubs.

Section 1: SALIX

These are:

- Salix pentandra or Bay Willow and see here

A dioecious multi-stemmed shrub or small tree of damp or wet base- and nutrient-poor soils, mostly in marshes, fens, mires and wet woodlands, and occasionally in winter-flooded dune-slacks and by ponds and streams, quarries and waste ground; historically, the more attractive male trees have been widely planted both within and outside its native range, often in hedges and on roadsides, as well as in amenity plantations and parks.

The foliage is the food plant for the larvae of several species of moth, including Ectoedemia intimella whose larvae mine the leaves. The catkins are attractive to bees and other insects for the nectar and pollen they produce early in the year. This willow is susceptible to watermark disease, which causes branches to die back, and is caused by the pathogenic bacterium Brenneria salicis.

- S. x meyeriana (Salix alba × euxina × pentandra ) or Shiny-leaved Willow. (A cultivated hybrid (native × alien) in Britain and Ireland)

- S. euxina or Eastern Crack Willow (neophyte)

A medium-sized or occasionally tall deciduous tree up to 15–18 m that only appears to be present as male clones in our area. Found along rivers, often on shingle within the spate zone, where it is unlikely to have been planted and may have regenerated from branches and twigs washed down rivers during floods.

- S. x fragilis or Hybrid Crack Willow: It is a hybrid between Salix euxina (see above) and Salix alba (see below), and is very variable, with forms linking both parents.

A large, broad-crowned, often pollarded, deciduous tree which has been widely planted along rivers, streams and ditches, around ponds, lakes and reservoirs and in drier sites such as hedgerows but also occurring more naturally in marshes, fens, and wet woodland.

- S. alba or White Willow (archaeophyte in Britain and the Channel Islands and a neophyte in Ireland))

A large deciduous tree which grows in marshes and wet hollows, by reedbeds, ponds, flooded pits, ditches, streams, rivers, canals, water-meadows, and woodland with damp, fertile, base-rich soils. It also appears in ruderal situations such as on waste and industrial land and along the rail and road networks. Usually planted but it can be self-sown in disturbed wetland habitats. Both male and female plants occur, but there is little information to indicate their relative abundance and distribution.

Varieties, cultivars and hybrids

Several cultivars and hybrids have been selected for forestry and horticultural use:

- Salix alba ‘Caerulea’ (cricket-bat willow; syn. Salix alba var. caerulea (Sm.) Sm.; Salix caerulea Sm.) is grown as a specialist timber crop in Britain, mainly for the production of cricket bats, and for other uses where a tough, lightweight wood that does not splinter easily is required. It is distinguished mainly by its growth form, very fast-growing with a single straight stem, and also by its slightly larger leaves (10–11 cm long, 1.5–2 cm wide) with a more blue-green colour. Its origin is unknown; it may be a hybrid between white willow and crack willow, but this is not confirmed.

- Salix alba ‘Vitellina’ (Golden willow; syn. Salix alba var. vitellina (L.) Stokes) is a cultivar grown in gardens for its shoots, which are golden-yellow for one to two years before turning brown. It is particularly decorative in winter; the best effect is achieved by coppicing it every two to three years to stimulate the production of longer young shoots with better colour. Other similar cultivars include ‘Britzensis’, ‘Cardinal’, and ‘Chermesina’, selected for even brighter orange-red shoots.

- Salix alba ‘Vitellina-Tristis’ (Golden weeping willow, synonym ‘Tristis’) is a weeping cultivar with yellow branches that become reddish-orange in winter. It is now rare in cultivation and has been largely replaced by Salix x sepulcralis ‘Chrysocoma’. It is, however, still the best choice in very cold parts of the world, such as Canada, the northern US, and Russia.

- Salix × sepulcralis ‘Chrysocoma’ (Golden hybrid weeping willow) is a hybrid between white willow and Peking willow Salix babylonica.

Award of Garden Merit

The following have received the Royal Horticultural Society‘s Award of Garden Merit

- Salix alba ‘Golden Ness’

- Salix alba var. serica (silver willow)

- Salix alba var. vitellina ‘Yelverton’

- Salix × sepulcralis ‘Erythroflexuosa’

- Salix × sepulcralis var. chrysocoma

Different uses:

The wood is tough, strong, and light in weight, but has minimal resistance to decay. The stems (withies) from coppiced and pollarded plants are used for basket-making. Charcoal made from the wood was important for gunpowder manufacture. The bark tannin was used in the past for tanning leather. The wood is used to make cricket bats.

S. alba wood has a low density and a lower transverse compressive strength. This allows the wood to bend, which is why it can be used to make baskets. Willow bark contains indole-3-butyric acid, which is a plant hormone stimulating root growth; willow trimmings are sometimes used to clone rootstock in place of commercially synthesized root stimulator. It is also used for ritual purposes by Jews on the holiday of Sukkot.

Medicinal uses:

Willow (of unspecified species) has long been used by herbalists for various ailments, although it is a myth that they attribute to it any analgesic effect. One of the first references to White Willow specifically was by Edward Stone, of Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, England, in 1763. He ‘accidentally’ tasted the bark and found it had a bitter taste, which reminded him of Peruvian Bark (Cinchona), which was used to treat malaria. After researching all the ‘dispensaries and books on botany,’ he found no suggestion of willow ever being used to treat fevers and decided to experiment with it himself. Over the next seven years he successfully used the dried powder of willow bark to cure ‘agues and intermittent fevers’ of around fifty people, although it worked better when combined with quinine.

Stone appears to have been largely ignored by the medical profession and herbalists alike. There are reports of two pharmacists using the remedy in trials, but there is no evidence that it worked. By the early 20th century, Maud Grieve, an herbalist, did not consider White Willow to be a febrifuge. Instead, she describes using the bark and the powdered root for its tonic, antiperiodic and astringent qualities and recommended its use in treating dyspepsia, worms, chronic diarrhoea and dysentery. She considered tannin to be the active constituent.

An active extract of the bark, called salicin, after the Latin name Salix, was isolated to its crystalline form in 1828 by Henri Leroux, a French pharmacist, and Raffaele Piria, an Italian chemist, who then succeeded in separating out the acid in its pure state. Salicylic acid is a chemical derivative of salicin and is widely used in medicine. Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is, however, a chemical that does not occur in nature and was originally synthesised from salicylic acid extracted from Meadowsweet, and is not connected to willow.

- S. triandra or Almond Willow and pfaf. (archaeophyte)

A deciduous shrub or small bushy tree, found in damp or wet places, by rivers, streams, old flooded pits and ponds and in marshes, osier-beds and old river diggings. Usually planted but occasionally self-sown. Both sexes occur but their relative abundance and distribution is not known.

Cultivation and uses:

The plant is a potential biomass source for biofuel energy generation.

In the Russian honey industry, the plant is used as a nectar source for honeybees. Basket weaving

The shoots (withies) are extensively used for basketmaking. It is one of the most important willows for this purpose after Salix viminalis, with several selected cultivars including: ‘Black Maul’, ‘Grizette’, ‘Mottled Spaniards’, ‘Sarda’, and ‘Yellow Dutch’.

Woven withies have been used in the creation of the large outdoor sculpture “Willow Man“, located near Bridgwater in England.

Section 2: VETRIX (SHRUBS OR SMALL TREES)

A variable shrub or small tree of wet ground on woodland margins, damp hillsides, by pools, ditches, gravel-pits, streams and rivers, on river shingle, in marshes and fens, and sometimes planted as an osier, as well as in roadside hedges and screening.

The weeping cultivar ‘Pendula’ has gained the Royal Horticultural Society‘s Award of Garden Merit. As with several other willows, the shoots, called withies, are often used in basketry. The wood of this and other willow species is used in making cricket bats.

- S. viminalis or Osier (arch.) and see Woodland Trust

A deciduous shrub or small tree, frequently coppiced and pollarded, which grows in damp places, by rivers, streams, canals, ponds and lakes, in wet woodland, marshes, fens, osier-beds, ditches and old flooded gravel-pits. Found mainly on wet soils of intermediate base status and fertility but also occurs in drier areas such as on waste ground and increasingly planted on roadsides and in hedges and landscaped areas in parks and gardens.

Along with other related willows, the flexible twigs (called withies) are commonly used in basketry, giving rise to its alternative common name of “basket willow”. Cultivation and use of the common osier was common in England in the 18th and 19th century, with osier beds lining many rivers and streams.

Other uses occur in energy forestry, effluent treatment, wastewater gardens, and cadmium, phytoremediation for water purification.

Salix viminalis is a known hyperaccumulator of cadmium, chromium, lead, mercury, petroleum hydrocarbons, organic solvents, MTBE, TCE and byproducts, selenium, silver, uranium, and zinc, and as such is a prime candidate for phytoremediation. For more information, see the list of hyperaccumulators.

- S. x smithiana (Salix viminalis × caprea) or Broad-leaved Osier

An erect shrub or small tree rarely up to 10 m high, which is found in mature vegetation in wet woodland (including ditches alongside forestry plantations), osier beds, carr by lakes and reservoirs, hedges, on canal and riversides, stream and ditch banks and in marshes and damp pastures, as well as in open early successional habitats such as sand- and gravel-pits, and waste ground. In many areas it occurs both as a spontaneous hybrid and as a relic of cultivation.

- S. x calodendron (Salix caprea x cinerea x viminalis ) or Holme Willow

- S. x stipularis (Salix aurita x caprea x viminalis) or Eared Osier

- S. x holosericea (Salix viminalis x cinerea) or Silky-leaved Osier

- S. x fruticosa (Salix aurita x viminalis) or Shrubby Osier

- S. caprea or Goat Willow and PFAF

A shrub or tree of open woodland and wood margins, scrub and hedgerows, damp meadows and fens, and the banks of rivers, ditches and streamsides. It colonizes waste ground and can tolerate drier and more base-rich soils than S. cinerea.

Hybrids with several other willow species are common, notably with Salix cinerea (S. × reichardtii), Salix aurita (S. × multinervis), Salix viminalis (S. × smithiana), and Salix purpurea (S. × sordida). Populations of S. caprea often show hybrid introgression.

Unlike almost all other willows, pure specimens do not take root readily from cuttings; if a willow resembling the species does root easily, it is probably a hybrid with another species of willow.

The leaves are used as a food resource by several species of Lepidoptera, and are also commonly eaten by browsing mammals. Willows are very susceptible to gall inducers, and the midge Rhabdophaga rosaria forms the camellia gall on S. caprea

- S. cinerea or Grey Willow and PFAF and NBN

- S. x laurina (Salix cinerea x phylicifolia) or Laurel-leaved Willow and here

- S. aurita or Eared Willow or here or brc.

- S. myrsinifolia or Dark-leaved Willow

- S. phylicifolia or Tea-leaved Willow

- S. repens or Creeping Willow and PFAF

- S. lapponum or Downy Willow or here

- S. lanata or Woolly Willow and PFAF

- S. arbuscula or Mountain Willow or here

Section 3 is CHAMAETIA, which are all Dwarf shrubs and has only got 3 (native) species.

- S. myrsinites or Whortle Leaved Willow

- S. herbacea or Dwarf Willow and brc.

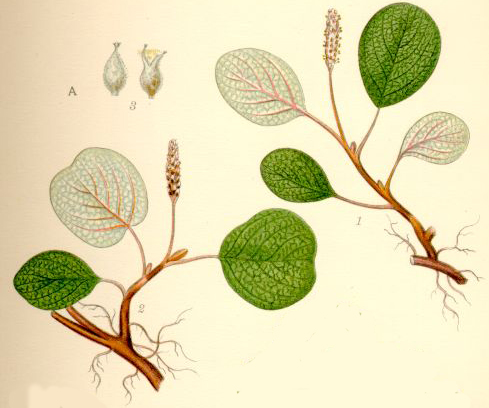

- S. reticulata or Net Leaved Willow

Much of the below information comes from Wikipedia. But for easy reading I will edit the information into bullet points as far as possible.

General information:

Willows, also called Sallows, and Osiers, form the genus Salix which are around 400 species of deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist soils in cold and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Most species are known as Willow, but some narrow-leaved shrub species are called Osier, and some broader-leaved species are referred to as Sallow (from Old English sealh, related to the Latin word salix, willow). Some willows (particularly arctic and alpine species) are low-growing or creeping shrubs; for example, the Dwarf Willow (Salix herbacea) rarely exceeds 6 cm (2.4 in) in height, though it spreads widely across the ground.

Ornamental Use:

Several native willows are attractive enough to plant in the garden or for the rockery if it is a Dwarf Willow!

Salix caprea ‘Kilmarnock’ or Kilmarnock Weeping Willow

This is a stiffly pendulous small tree with yellowish branches, ovate leaves, and large grey catkins with yellow anthers opening before the leaves. You can watch this Youtube film in order how to prune it after flowering.

Salix babylonica or Weeping Willow is a commonly planted tree in large parks or gardens and especially looking good in early spring near water with its large lime-green foliage nearly touching the water. It is however not native.

There are several other ornamental willows, usually not native species such as :

Salix matsudana ‘Tortuosa’ or Corkscrew Willow

Salix udensis ‘Sekka’ or Japanese Fantail Willow

An article especially about Weeping Willows and other ornamental willows can be found here.

- The leaves and bark of the Willow tree have been mentioned in ancient texts from Assyria, Sumer and Egypt as a remedy for aches and fever, and in Ancient Greece the physician Hippocrates wrote about its medicinal properties in the fifth century BC!

- Native Americans across the Americas relied on it as a staple of their medical treatments. It provides temporary pain relief.

- Salicinis metabolized into salicylic acid in the human body, and is a precursor of aspirin.

- Willows produce a modest amount of nectar from which bees can make honey, and are especially valued as a source of early pollen for bees.

- Poor people at one time often ate willow catkins that had been cooked to form a mash.

Manufacturing and historical uses:

Some of the human race’s earliest manufactured items have been made from Willow.

- A fishing net made from Willow dates back to 8300 BC. Basic crafts, such as baskets, fish traps, wattle fences and wattle and daub house walls, were often woven from Osiers or Withies (rod-like Willow shoots, often grown in coppices).

- One of the forms of Welsh coracle boat traditionally uses Willow in the framework.

- Thin or split Willow rods can be woven into wicker, which also has a long history. The relatively pliable Willow is less likely to split whilst being woven than many other woods, and can be bent around sharp corners in basketry.

- Willow wood is also used in the manufacture of boxes, brooms, cricket bats, cradle boards, chairs and other furniture, dolls, flutes, poles, sweat lodges, toys, tool handles, veneer, wands and whistles.

- In addition, tannin, fibre, paper, rope and string can be produced from the wood.

- Willow is also used in the manufacture of double basses for backs, sides and linings, and in making splines and blocks for bass repair.

- Willows are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species, such as the mourning cloak butterfly. Ants, such as wood ants, are common on Willows inhabited by aphids, coming to collect aphid honeydew, as sometimes do wasps.

- As mentioned earlier, most of the Willows are a good early source of pollen and nectar for bees.

- The thinner stemmed willows are used for weaving baskets

- Willow is used to make charcoal (for drawing)

- Living sculptures are created from live Willow rods planted in the ground and woven into shapes such as domes and tunnels.

- Willow stems are also used to create garden features, such as decorative panels, obelisks and garden constructions such as bowers.

Almost all Willows take root very readily from cuttings or where broken branches lie on the ground. The few exceptions include the Goat Willow (Salix caprea) and Peachleaf Willow (Salix amygdaloides).

One famous example of such growth from cuttings involves the poet Alexander Pope, who begged a twig from a parcel tied with twigs sent from Spain to Lady Suffolk. This twig was planted and thrived and legend has it that all of England’s Weeping Willows are descended from this first one.

Willow is grown for biomass or biofuel, in energy forestry systems, as a consequence of its high energy in/energy out ratio, large carbon mitigation potential and fast growth. Large-scale projects to support Willow as an energy crop are already at commercial scale in Sweden. Programs in other countries are being developed through initiatives such as the Willow Biomass Project in the US, and the Energy Coppice Project in the UK.

- biofiltration

- constructed wetlands

- ecological wastewater treatment systems

- hedges

- land reclamation

- landscaping

- phytoremediation

- streambank stabilisation (bioengineering)

- slope stabilisation & soil erosion control

- shelter-belt and windbreak

- soil building & soil reclamation

- tree bog compost toilet and

- wildlife habitat.

Willows are often planted on the borders of streams, so their interlacing roots may protect the bank against the action of the water. Frequently the roots are much larger than the stem which grows from them.

Willow is one of the “Four Species” used ritually during the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. In Buddhism, a Willow branch is one of the chief attributes of Kwan Yin, the bodhisattva of compassion. Christian churches in northwestern Europe and Ukraine and Bulgaria often used Willow branches in place of palms in the ceremonies on Palm Sunday.

Pollarding: A pruning system involving the removal of the upper branches of a tree, promotes a dense head of foliage and branches. In ancient Rome, Propertius mentioned pollarding during the 1st century BC. The practice has occurred commonly in Europe since medieval times and takes place today in urban areas worldwide, primarily to maintain trees at a predetermined height.

In my native lowland Holland, willows are often seen neatly pollarded along roads, ditches and rivers. Usually Salix alba is used for this. This is traditional and aesthetical as well as practical when the water table is mostly very high and in combination with strong winds, tall trees would just keel over!

The form Salix alba var. vitellina ‘Britzensis’ can also be seen with its glowing orange red stems in winter.

Traditionally, people pollarded trees for one of two reasons:

For fodder to feed livestock or for wood.

- Fodder pollards produced “pollard hay”, which was used as livestock feed; they were pruned at intervals of two to six years so their leafy material would be most abundant.

- Wood pollards were pruned at longer intervals of eight to fifteen years, a pruning cycle that tended to produce upright poles favoured for fence rails and posts, as well as for boat construction.

One positive consequence of pollarding is that pollarded trees tend to live longer than unpollarded specimens because they are maintained in a partially juvenile state and because they do not have the weight and windage of the top part of the tree.

Older pollards often become hollow, so can be difficult to age accurately. However an interesting garden can grow inside those old crowns!

Pollards tend to grow slowly, with narrower growth rings in the years immediately after cutting.

Unusual non native willow in Sutton Park:

Salix eriocephala or Missouri River willow or Heart-leaved Willow, was recently found in Sutton Park as a non native species.